Oklahoma

On its beeline to Texas, US-83 doesn’t just cross Oklahoma, it forsakes it, merely nipping the panhandle for a 37-mi (60-km) dash. When crossing the border 3 mi (4.8 km) south of Liberal, among the first things you see are a vape store, a used-car lot, and a bingo hot spot. They’re inauspicious sights at best. And that’s not even mentioning the slate-flat, wicked badlands, with temperatures high enough in summer to occlude your vision of the blistering pavement and preclude a drive at top speeds.

After a while, you’re unable to conjure up synonyms for “endless,” though there’s plenty of time for it. Even the historical marker you think you eventually see winds up being in Texas.

The Dust Bowl

Though it may not have been the biggest migration in U.S. history, it was certainly the most traumatic—entire families packing up their few belongings and fleeing the Dust Bowl of the Depression-era Great Plains. Beginning in 1930 and continuing year after year until 1940, a 400-mile-long, 300-mile-wide region roughly bisected by US-83—covering 100 million acres of western Kansas, eastern Colorado, and the panhandles of Oklahoma and Texas—was rendered uninhabitable as ceaseless winds carried away swirling clouds of what had been agricultural land.

The “Dust Bowl,” as it was dubbed by Associated Press reporter Robert Geiger in April 1935, was caused by a fatal combination of circumstances. This part of the plains was naturally grassland and had long been considered marginal at best, but the rise in agricultural prices during and after World War I made it profitable to till and plant. Farmers invested in expensive machinery, but when the worldwide economic depression cut crop and livestock prices by as much as 75 percent, many farmers fell deeply into debt. Then, year after year of drought hit the region, and springtime winds carried away the fragile topsoil, lifting hundreds of tons of dust from each square mile, and dropping it as far east as New York City.

By the mid-1930s, many of the farmers had been forced to abandon their land, and while some were able to rely on a series of New Deal welfare programs, many more fled for California and the Sunbelt states. In this mass exodus, as recorded by photographers like Dorothea Lange and most memorably in John Steinbeck’s 1939 novel The Grapes of Wrath, some 100,000 people each year packed up their few possessions and headed west, never to return.

Nowadays, thanks to high-powered pumps that can reach down to the Ogalala Aquifer, much of what was the Dust Bowl is once again fertile farmland, no longer as dependent on the vicissitudes of the weather. Much of the rest of the land was bought up by the U.S. government, and some four million acres are now protected within a series of National Grasslands that maintain the Great Plains in more or less their natural state.

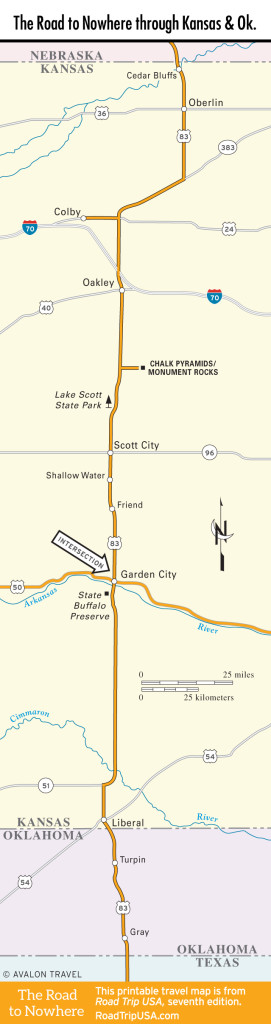

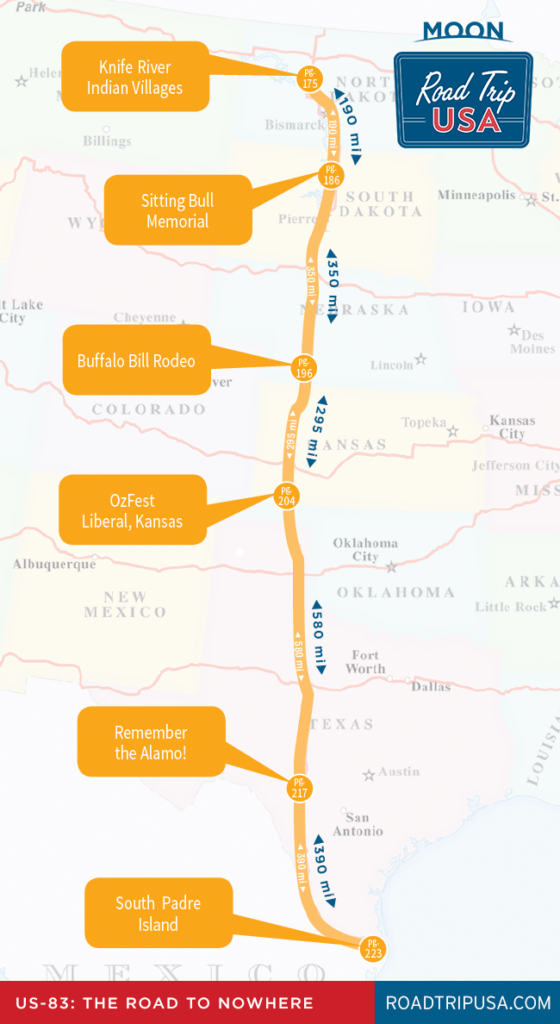

Travel Map of the Road to Nowhere through Kansas and Oklahoma