Standing Rock Indian Reservation: Fort Yates

Huge hills appear around the Standing Rock Indian Reservation, home to approximately 8,500 Sioux people and spreading across the state line with a total of 2.3 million ac (930,777 ha). In 2016, Standing Rock became a flashpoint in the battle between the “fracking” fossil-fuel industry and environmental activists known as “water protectors,” who rallied here to prevent an oil pipeline under the Missouri River. At its peak more than 3,000 protesters set up camp along the Missouri River and Hwy-1806, near the Cannon Ball Bridge.

Along with fantastic roadside views, connections to Sioux traditions, and the travels of Lewis and Clark, the main draw to the reservation is its namesake Standing Rock, which stands in the town of Fort Yates (pop. 199), along the riverfront near the tribal headquarters. In the correct angle of sunlight, the stone resembles a seated woman wearing a shawl. Legend holds that the woman, jealous of her husband’s second wife, refused to move when the Sioux decamped; a search party later found her, turned to stone.

Fort Yates also once held the original burial site of Sitting Bull, who was killed here in 1890, but the unimpressive site, marked by a boulder on a dusty side road two miles (3.2 km) west of Hwy-1806, is certainly not what one would expect for the great Sioux warrior. After his family exhumed his remains in 1953, Sitting Bull is now more suitably interred and memorialized near his birthplace in Mobridge, South Dakota, on the Standing Rock Reservation 50 mi (81 km) to the south.

South of Fort Yates, the scenery and the driving (or riding) are magnificent. Flawless blacktop winds through valleys and up ambitious swooping hills of grazing land. You’ll be confronted by one gorgeous landscape after another, especially at dusk, when the intense Western sun illuminates the bands of sunflower fields, turns the dry and grassy hills a reddish shade of ocher, and casts angular shadows beneath the darting sandpipers, who whisk their brown-and-white forms along the roadway, buzzing the lone car on the road in an extended game of highway tag.

You won’t even realize you’re in South Dakota until you notice the gold border on the highway signs. The actual border between North and South Dakota was marked by 720 stone monuments, each 7 ft (2.1 m) tall but half-buried in the ground every half-mile (0.8 km). They were erected by the federal government around 1892. While many have been destroyed or removed, they are currently the focus of preservation efforts.

Related Travel Guides for the Road to Nowhere

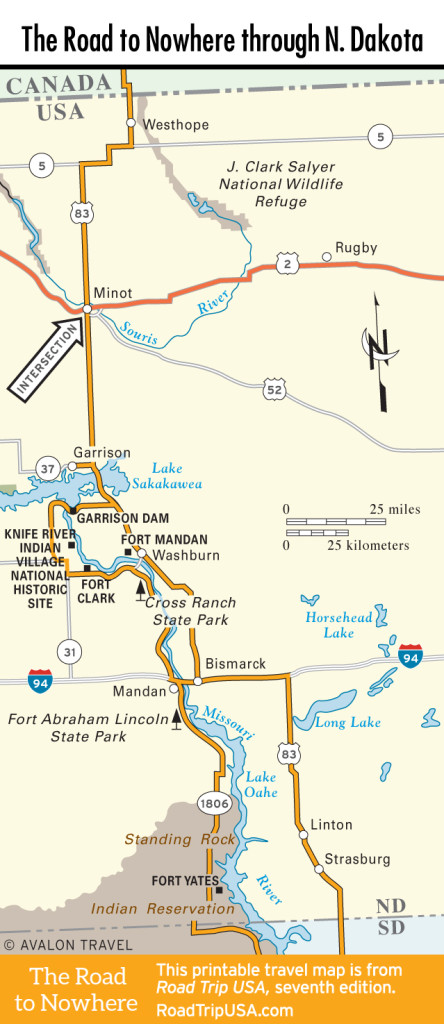

Travel Map of the Road to Nowhere through North Dakota