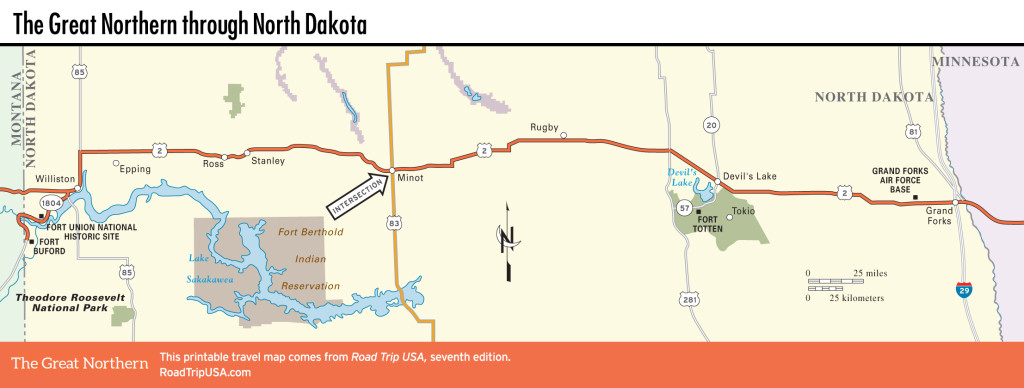

Fort Union Trading Post to Williston

Fort Union Trading Post

Astride the Montana-North Dakota border, standing proud atop the banks at the confluence of the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers, the Fort Union Trading Post National Historic Site was once the largest and busiest outpost on the upper Missouri River. Despite the “fort” in its name, it was never a part of the U.S. military; it was, however, the most successful and longest-lived of all the frontier trading posts. In 1804, Lewis and Clark visited the site, which they called “a judicious position for the purpose of trade.” Twenty-five years later, John Jacob Astor’s American Fur Company proved them right, establishing an outpost here in a successful attempt to end the Hudson Bay Company’s monopoly on northwest trade. Linked by steamboat with St. Louis some 1,800 miles (2,897 km) away, Fort Union reigned over the northern plains. Its bon vivant overseer, Kenneth McKenzie, the “King of the Missouri,” kept the fine china polished and the wines cool in the cellar, offering a taste of displaced civilization to such luminary explorers as George Catlin, Prince Maximilian, and John James Audubon.

The fort was abandoned as the fur trade declined in the 1850s, and portions of original buildings and walls were taken down by the U.S. Army in 1867 to construct Fort Buford, a mile (1.6 km) to the east. In the late 1980s, the National Park Service reconstructed the buildings atop the original foundations, giving a palpable if somewhat overly polished idea of how the old fort looked. McKenzie’s old home and office, Bourgeois House, is now a visitors center (701/572-9083, daily, donation) with some surprising artifacts. The fort hosts occasional reenactments of boisterous frontier life: Mid-June, for example, brings the annual Fort Union Rendezvous, a rollicking re-creation of fur-trapper gatherings to trade, talk, and compete in wilderness skills.

Fort Buford

Built in 1866 and now a state historic site, Fort Buford is eerily quiet, with only the stone powder magazine, a cemetery site, and a museum in an original soldiers’ quarters open for viewing. South of Fort Union, and once home to a company of “Buffalo Soldiers,” as the Sioux called the African-American cavalrymen, the fort is best known for its sad contribution to the U.S. campaign to exterminate Native Americans: It was here that Chief Sitting Bull surrendered to the U.S. Army in 1881, and here that Chief Joseph of the Nez Percé was brought after his surrender in Montana.

Williston

Just north of Lake Sakakawea and the Missouri River, a dozen miles east of the Montana line, Williston (pop. 27,096) has always been a boom or bust kind of place, and in recent years it has been enjoying a boom in its primary industries—wheat-growing and oil-pumping—which by some measures made it the fastest-growing small town in the USA for a time. Motels are often booked up by crews of “fracking Bakken” oil field workers, but the downtown area is still an all-American scene straight out of Our Town.

Apart from filling the tank before a trip to Fort Union or farther afield, one more good thing to do in Williston is eat: Responding to an impromptu poll, locals will likely recommend the classic truck stop Lonnie’s Roadhouse Cafe (226 42nd St., 701/774-1103), north of downtown, or will point you toward Big Willy’s Saloon & Grill (3701 4th Ave. W., 701/577-3703) as the eatery of choice. Big Willy’s is famous for its “Frac-Attack”: a double-height grilled cheese sandwich split by a full 1-lb burger, all yours for $25. (You get a chance at a free T-Shirt if you finish it off in less than 30 minutes.)