Glacier National Park

The wildest and most rugged of all the Rocky Mountain national parks, Glacier National Park protects some 1,500 sq mi (3,885 sq km) of high-altitude scenery, including hundreds of lakes and countless rivers and streams. Knifelike ridges of colorful sedimentary rock rise to over 10,000 feet, looming high above elongated glacier-carved valleys. Grizzly bears, black bears, bighorn sheep, mountain lions, and wolves roam the park’s wild backcountry, which is crisscrossed by some 740 mi (1,190 km) of hiking and riding trails.

If you want to see the glaciers for which the park is named, you need to act fast: a warming climate has shrunk the glaciers to less than half their historic sizes, and forecasts say they may disappear completely with five years.

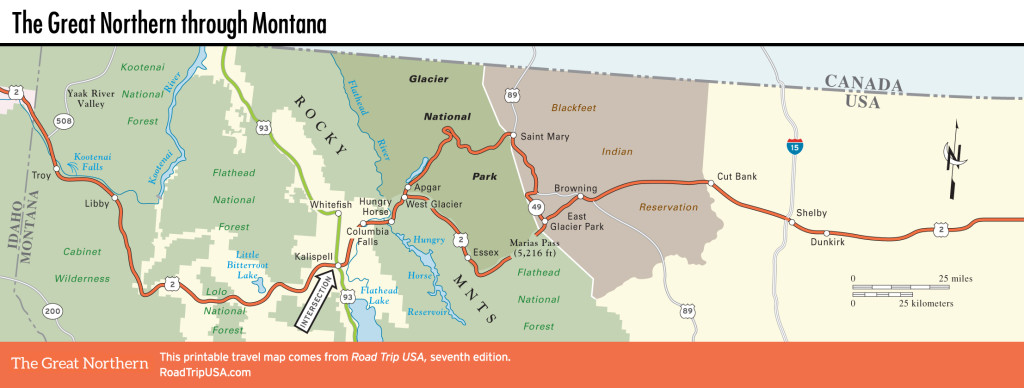

The park’s main features are reached via 50-mi-long (82-km) Going-to-the-Sun Road, a magnificent serpentine highway that is arguably the most scenic route on this planet. Climbing up from dense forests to the west and prairie grasslands to the east, this narrow road (built in 1932, and currently undergoing a multiyear rehabilitation project) is the only route across the park’s million acres (404,686 hectares).

Note that the road’s middle section—everything east of Lake McDonald, basically—is usually closed by snow from late October until early June. RV drivers note: No vehicles or combinations over 21 feet are allowed on the Going-to-the-Sun Road.

On the west side of the park, lovely Lake McDonald is Glacier’s largest lake, and also the most developed area, with an attractive lodge, two restaurants, a gas station, and a nice campground. A boat offers hour-long narrated tours throughout the summer. Between the lake and Logan Pass, Avalanche Creek is the most beautiful short hike in the park, winding through dense groves of cedar and fir alongside a creek that cascades noisily down a sharp cleft in the deep red rock. The 2-mile (3.2-km, one-way) trail ends up at Avalanche Lake, hemmed in by 1,500-ft-high (457-m) cliffs.

The heart of the park is Logan Pass, a 6,646-ft (2,025-m) saddle straddling the Continental Divide, which comes alive when the snow melts to reveal a rainbow of brightly colored wildflowers. Two popular trails run from the large visitors center: The shorter but more strenuous one heads south on a wooden boardwalk across an alpine meadow to a viewpoint overlooking Hidden Lake, while the fairly flat Highline Trail runs north, high above the Going-to-the-Sun Road, leading 7 mi (11.3 km) to the backcountry Granite Park Chalet (888/345-2649, $115 per person) where you can stay overnight in a spectacular setting. Bed linens and simple meals are available for additional fees, or you can bring your own sleeping bags and food.

Along with the extensive privately owned facilities just outside the park along US-2 at West Glacier, East Glacier, and St. Mary, there are a number of rustic lodges and motels within the park. Apart from the chalets, all lodging (and everything else) in Glacier is run by the same concessionaire, Xanterra (303/265-7010 or 855/733-4522). The nicest place to stay is the intimate, comfortable Lake McDonald Lodge, with a lovely lobby filled with comfy chairs arrayed around a fireplace, and lots of bearskin and buffalo rugs.

In the park’s northeast corner, the Many Glacier Lodge is a circa-1915 pseudo-Swiss chalet on the shores of Swiftcurrent Lake, looking up at Grinnell Point. There are over a dozen campgrounds in Glacier, but they fill up fast.

Besides the grand lodges, a few other relics of Glacier Park’s early days as a “Grand Tour” destination still survive: bright red, open-top, vintage 1930s touring buses, expensively overhauled to be as eco-friendly as possible, run along the Going-to-the-Sun Road, providing enjoyable guided tours as well as a shuttle service for hikers.

For a complete overview of the park, stop in at one of three main visitors centers, located in West Glacier, at Logan Pass (summer only), and at the eastern entrance in the town of St. Mary; or call the park headquarters (406/888-7800 or 406/888-7931).