Savannah

Named the “Most Beautiful City in North America” by the Parisian newspaper and style arbiter Le Monde, Savannah (pop. 145,862) is a real jewel of a place. Founded in 1733 as the first settlement in Georgia, the 13th and final American colony, Savannah today preserves its original neoclassical, colonial, and antebellum self in a welcoming, unselfconscious way. Famous for having been spared by General Sherman on his destructive March to the Sea at the end of the Civil War, it was here that Sherman made his offering of “40 acres and a mule” to all people freed from slavery.

Before and after the war, Savannah was Georgia’s main port, rivaling Charleston, South Carolina, for the enormously lucrative cotton trade, but as commercial shipping tailed off, the harbor became increasingly recreational—the yachting competitions of the 1996 Olympics were held offshore. Savannah, home of writer Flannery O’Connor and songsmith Johnny Mercer, also served as backdrop to the best-selling book Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil and numerous movies, most famously Forrest Gump, but it has resisted urges to turn itself into an “Old South” theme park; you’ll have to search hard to find souvenir shops or overpriced knickknack galleries. The city is in such good shape partly thanks to the Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD), which has taken over many of the city’s older buildings and converted them into art studios, galleries, and cafés.

At the center of Savannah, midway down Bull Street between the waterfront and spacious Forsyth Park, Chippewa Square was the site of Forrest Gump’s bus bench; the movie prop was moved to the Savannah History Museum (303 MLK Jr. Blvd., 912/651-6825, 9am-5:30pm daily, $9) and may one day be erected in bronze. Reynolds Square, near the waterfront, has a statue of John Wesley, who lived in Savannah in 1736-1737 and established the world’s first Sunday school here. Wright Square holds a monument to Chief Tomochichi, the Native American leader who allowed Georgia founder James Edward Oglethorpe to settle here. At the south edge of the historic center, Forsyth Park, inspired by the Place de la Concorde in Paris, is surrounded by richly scented magnolias.

Another great place to wander is Factor’s Walk, a promontory along the Savannah River named for the “factors” who controlled Savannah’s cotton trade. This area holds the Cotton Exchange and other historic buildings, many of them constructed from 18th-century ballast stones. Linked from the top of the bluffs by a network of steep stone stairways and cast-iron walkways, River Street is lined by restaurants, and at the east end there’s a statue of a girl waving a cloth; it was erected in memory of Florence Martus, who for 44 years around the turn of the 20th century greeted every ship entering Savannah harbor in the vain hope that her boyfriend would be on board.

March is when things get crazy here in Savannah: Thousands of visitors come to the bars along Congress Street for what has grown into the world’s second-largest St. Patrick’s Day celebration—only New York City’s is bigger.

One of Savannah’s more unusual tourist attractions is the Juliette Gordon Low Birthplace (10 E. Oglethorpe Ave.), a circa-1820 house that was the childhood home of the woman who introduced Girl Scouts to America in 1912.

Where to Eat and Stay in Savannah

Getting around is blissfully easy: Savannah is the country’s preeminent walkers’ town, with a wealth of historic architecture and a checkerboard of 22 small squares shaded with centuries-old live oak trees draped with tendrils of Spanish moss, all packed together in a single square mile. Savannah’s sensible and attractive modified grid plan makes finding your way so simple that it’s almost fun to try to get lost.

For an unforgettable midday meal, be sure to stop at Mrs. Wilkes’ Dining Room (107 W. Jones St., 912/232-5997, 11am-2pm Mon.-Fri. Feb.-Dec., all you can eat $25), a central Savannah home and former boardinghouse that still offers up seasonal, traditional family-style Southern cooking—varying from fried chicken to beef stews, with side dishes like okra gumbo, blueberry pie, red or brown rice, and cornbread. It’s worth a trip from anywhere in the state—don’t leave Savannah without eating here. For a more upscale take on these Deep South classics, make plans to have lunch or dinner at The Olde Pink House (23 Abercorn St., 912/232-4286), on Reynolds Square. For an only-in-Savannah mix of Mississippi barbecue in a vintage New England diner, step inside the 1930s Worcester Lunch Car, housing the Sandfly BBQ (1220 Barnard St., 912/335-8058, Mon.-Sat.).

Places to stay in Savannah vary from quaint B&B inns to stale high-rise hotels. For the total Savannah experience, try the Bed and Breakfast Inn (117 W. Gordon St., 912/238-0518, $99 and up), which has nice rooms in an 1853 townhouse off Monterey Square. At the River Street Inn (124 E. Bay St., 912/234-6400, $149 and up), well-appointed rooms fill a converted antebellum cotton warehouse, right on Factor’s Walk at the heart of the Savannah riverfront. Nearby, the large Hotel Indigo (201 W. Bay St., 912/236-4440, $140 and up) has good-size hotel rooms (in the former Inn at Ellis Square) a few blocks from Factor’s Walk.

The main Savannah visitors center (301 Martin Luther King Blvd., 912/944-0455), in the old Georgia Central railroad terminal in the historic district, has free maps and brochures and other information on the city.

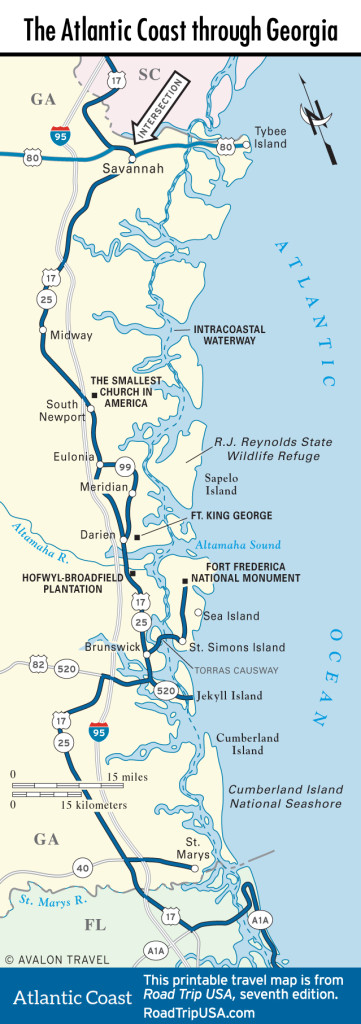

Related Travel Map